Age-based investing has become an efficient way for financial services companies to sell investments.

Take target-date funds and, more broadly, retirement planning—the prime example of the age-based investing approach in action. All you need to know is your current age and expected retirement year and—presto—you can buy into an asset allocation fund designed just for "you" and your shifting-with-age risk tolerance.

You might not know the difference between large-cap stocks and momentum investing or senior floating-rate bank-loan products designed to hedge interest rates, but who doesn't know their own age, right?

Take target-date funds and, more broadly, retirement planning—the prime example of the age-based investing approach in action. All you need to know is your current age and expected retirement year and—presto—you can buy into an asset allocation fund designed just for "you" and your shifting-with-age risk tolerance.

You might not know the difference between large-cap stocks and momentum investing or senior floating-rate bank-loan products designed to hedge interest rates, but who doesn't know their own age, right?

The age-based investor rage does raise one big question:

Is it going to be as good to investors in the long run as it has been

lately for financial services companies?

According to many financial advisors, the answer to that question is no, with a few qualifications. Age-based investing is an important concept and has been extremely helpful in basic 401(k) planning—no small task—but advisors suggest it's woefully inadequate as a way for investors to frame their investing goals and won't result in goal attainment.

"The problem with age-based investing is, it takes the complex challenge of retirement investing and tries to make it overly broad," said Andrew Holland, managing director at Quantitative Investment Advisors & Co.

Wayne von Borstel, certified financial planner at von Borstel & Associates, was less subtle: "Age-based is terrible for investors and great for marketers, and it sells well because people think they fit into a category," he said. "People need to be looking for a plan, not an easy fix."

To that point, we have gathered a few of the biggest myths about age-based investing.

According to many financial advisors, the answer to that question is no, with a few qualifications. Age-based investing is an important concept and has been extremely helpful in basic 401(k) planning—no small task—but advisors suggest it's woefully inadequate as a way for investors to frame their investing goals and won't result in goal attainment.

"The problem with age-based investing is, it takes the complex challenge of retirement investing and tries to make it overly broad," said Andrew Holland, managing director at Quantitative Investment Advisors & Co.

Wayne von Borstel, certified financial planner at von Borstel & Associates, was less subtle: "Age-based is terrible for investors and great for marketers, and it sells well because people think they fit into a category," he said. "People need to be looking for a plan, not an easy fix."

To that point, we have gathered a few of the biggest myths about age-based investing.

Myth #1: Your age is a good indicator of your risk tolerance.

Age-based investing takes as its premise that your age is a good proxy for your risk tolerance, and your portfolio can shift over time between equities, fixed-income and cash based on your age. Dead wrong, some advisors say.

Portfolio structure—based on an investor's risk tolerance—should factor in three main considerations: your ability, your willingness and your need to take risk, said certified financial planner Tim Maurer, director of personal finance for the BAM Alliance.

Ability is partially based on the time horizon, and that's the single factor taken into account with target-date funds. But part of ability is also, such as an investor's stability of earned income.

Willingness is otherwise known as "the stomach acid test," and need is based on the return required to achieve your goals. How much are you willing to lose is as important a question as how much you need by retirement age.

Myth #2: All individuals of the same age act in a similar way.

Like ages think alike? Not necessarily.

Holland said that if a 25-year-old who doesn't know much about investing gets into a target-date fund and the portfolio is 90 percent equity-weighted, then declines 10 percent in a three-month period, that could trigger the investor to sell at a loss.

Worse, they could "be afraid of the markets for the rest of [their] life just because they have a low-risk tolerance," he said. "If you are just a nervous person, no matter how old you are, you will sell at loss."

Age-based investing takes as its premise that your age is a good proxy for your risk tolerance, and your portfolio can shift over time between equities, fixed-income and cash based on your age. Dead wrong, some advisors say.

Portfolio structure—based on an investor's risk tolerance—should factor in three main considerations: your ability, your willingness and your need to take risk, said certified financial planner Tim Maurer, director of personal finance for the BAM Alliance.

Ability is partially based on the time horizon, and that's the single factor taken into account with target-date funds. But part of ability is also, such as an investor's stability of earned income.

Willingness is otherwise known as "the stomach acid test," and need is based on the return required to achieve your goals. How much are you willing to lose is as important a question as how much you need by retirement age.

Myth #2: All individuals of the same age act in a similar way.

Like ages think alike? Not necessarily.

Holland said that if a 25-year-old who doesn't know much about investing gets into a target-date fund and the portfolio is 90 percent equity-weighted, then declines 10 percent in a three-month period, that could trigger the investor to sell at a loss.

Worse, they could "be afraid of the markets for the rest of [their] life just because they have a low-risk tolerance," he said. "If you are just a nervous person, no matter how old you are, you will sell at loss."

"Our job is to take fear away from people, but age-based takes it away in the wrong way."

Katherine Roy, chief retirement strategist at JPMorgan

Asset Management, said it doesn't make much sense to automatically

recommend to 30-year-olds that they be more aggressive at a time when

studies suggest at least some of them have a risk profile more like

65-year-olds, due to the Great Recession.

How you perceive risk outside of a market context may tell you a lot about how you will perceive risk in the markets, Roy said, and she pointed to work done by FinaMetrica as an example of the risk-profiling approach that takes into account both innate risk tolerance and risk perception.

"Individuals have an innate risk tolerance," Roy said. "Do you think danger or thrill when you think of risk?" It's a question FinaMetrica asks in its risk-profiling work. An investor also has to determine his or her risk capacity—which includes but is not limited to time horizon—and also how risk perception may change over time.

Events like the Great Recession proved that perception is a critical component of investment planning based on risk. For example, the 30-year-old and 65-year-old may not have the same innate risk tolerance, but they can still arrive at the same place—the 30-year-old due to perception and the 65-year-old because of risk capacity (or, in other words, age).

Read MoreWhich to pay: Student loan or 401(k)?

Even among the huge subset of older investors, there is a big difference between a person who has retired at 65 and a 65-year-old who is planning to work until 75. For older investors, von Borstel said to forget age and, instead, break it down to the four things you need at retirement:

How you perceive risk outside of a market context may tell you a lot about how you will perceive risk in the markets, Roy said, and she pointed to work done by FinaMetrica as an example of the risk-profiling approach that takes into account both innate risk tolerance and risk perception.

"Individuals have an innate risk tolerance," Roy said. "Do you think danger or thrill when you think of risk?" It's a question FinaMetrica asks in its risk-profiling work. An investor also has to determine his or her risk capacity—which includes but is not limited to time horizon—and also how risk perception may change over time.

Events like the Great Recession proved that perception is a critical component of investment planning based on risk. For example, the 30-year-old and 65-year-old may not have the same innate risk tolerance, but they can still arrive at the same place—the 30-year-old due to perception and the 65-year-old because of risk capacity (or, in other words, age).

Read MoreWhich to pay: Student loan or 401(k)?

Even among the huge subset of older investors, there is a big difference between a person who has retired at 65 and a 65-year-old who is planning to work until 75. For older investors, von Borstel said to forget age and, instead, break it down to the four things you need at retirement:

- To live on at least 3 percent of your wealth

- To have five years' worth of a total portfolio balance that you can live on (e.g., 60 months of a $3,000 monthly budget) in short-term bonds.

- No debt.

- A six-month emergency fund.

Myth #3: Target-date funds complete a portfolio.

"Age-based investing is a starting place," Roy said. Why? Because the one piece of information that a 401(k) plan has on all participants is their age—and it's the only thing a plan sponsor can be really confident about knowing. "Target-date funds are effective because of the limited information. ... If investors won't engage, there is not a better alternative, but with greater wealth and changing circumstances, a more thoughtful approach is advised."

Another positive of age-based investing, according to von Borstel, is that dealing with investors means dealing with emotional beings, and their biggest enemy is what they, and not the market, do. "If investors put money in and ignore it, they might do better than people who watch it ... but it's still not the best alternative," von Borstel said.

A glaring example of where target-date funds typically fall short of the more "thoughtful approach" is with alternative asset classes.

Equities, bonds and cash aren't enough, according to many advisors. Yet with most target-date funds, that is all an investor is going to have access to over the decades that the portfolio is on autopilot.

Holland said real estate and commodities need to be core asset classes alongside equities and bonds, but most of these target funds don't include access to either.

"Age-based investing is a starting place," Roy said. Why? Because the one piece of information that a 401(k) plan has on all participants is their age—and it's the only thing a plan sponsor can be really confident about knowing. "Target-date funds are effective because of the limited information. ... If investors won't engage, there is not a better alternative, but with greater wealth and changing circumstances, a more thoughtful approach is advised."

Another positive of age-based investing, according to von Borstel, is that dealing with investors means dealing with emotional beings, and their biggest enemy is what they, and not the market, do. "If investors put money in and ignore it, they might do better than people who watch it ... but it's still not the best alternative," von Borstel said.

A glaring example of where target-date funds typically fall short of the more "thoughtful approach" is with alternative asset classes.

Equities, bonds and cash aren't enough, according to many advisors. Yet with most target-date funds, that is all an investor is going to have access to over the decades that the portfolio is on autopilot.

Holland said real estate and commodities need to be core asset classes alongside equities and bonds, but most of these target funds don't include access to either.

Von Borstel also said that including real estate and

commodities is key and any target-date fund that shifts a retiree to a

90 percent weighting in bonds is "leading lambs to the slaughter." He

also recommends, on average, between 40 percent and 50 percent in

equities in retirement. (Some of the largest financial services

companies have upped their own recommendations and now advise similar

stock exposure for those in retirement.)

It's important to know if this more aggressive tilt later in life might be in your best interest—and if your target-date fund has made the move, too.

Roy explained that the old "equity, fixed-income and cash" three-asset-class pie chart can be enhanced within the confines of target-date funds—though alternative asset classes as stand-alone investments in most 401(k) plans would not be a change she supported.

"There is lots of debate today on whether there should be more alternatives in target-date funds, and we are seeing a move that way more so than historically," Roy said.

It's important to know if this more aggressive tilt later in life might be in your best interest—and if your target-date fund has made the move, too.

Roy explained that the old "equity, fixed-income and cash" three-asset-class pie chart can be enhanced within the confines of target-date funds—though alternative asset classes as stand-alone investments in most 401(k) plans would not be a change she supported.

"There is lots of debate today on whether there should be more alternatives in target-date funds, and we are seeing a move that way more so than historically," Roy said.

Eric RosenbaumCNBC.com

Roy

Laux, president of Synergy Financial Services in McKeesport, Pa., says

the first step in any financial planning is to establish an emergency

fund.

Roy

Laux, president of Synergy Financial Services in McKeesport, Pa., says

the first step in any financial planning is to establish an emergency

fund. If

you have credit card debt, student loan debt or medical bills, your

next priority should be to reduce and eventually eliminate that debt so

that your income can be channeled into saving and investing for the

future.

If

you have credit card debt, student loan debt or medical bills, your

next priority should be to reduce and eventually eliminate that debt so

that your income can be channeled into saving and investing for the

future. "In

your 40s, you should at least be saving as much in your 401(k) as your

employer matches," Laux says. "Even if you weren't making any profit on

that investment, your money doubles just because of the employer match."

"In

your 40s, you should at least be saving as much in your 401(k) as your

employer matches," Laux says. "Even if you weren't making any profit on

that investment, your money doubles just because of the employer match." In

addition to saving for retirement at work, Merrill Lynch's Corey

recommends making the maximum allowable contributions to a traditional

individual retirement account or a Roth IRA, depending on your income.

In

addition to saving for retirement at work, Merrill Lynch's Corey

recommends making the maximum allowable contributions to a traditional

individual retirement account or a Roth IRA, depending on your income. If

you're in your 40s and have kids, you may have already started saving

for their college tuition, depending on their age. The best advice from

financial advisers is to start saving as early as possible after your

kids are born, even if you can only save a small amount. Hopefully, you

can increase the amount you save for college as your income rises.

If

you're in your 40s and have kids, you may have already started saving

for their college tuition, depending on their age. The best advice from

financial advisers is to start saving as early as possible after your

kids are born, even if you can only save a small amount. Hopefully, you

can increase the amount you save for college as your income rises. "It's

important for people in their 40s to do an insurance-needs analysis,"

Corey says. "Often, people in this age group need a lot of life

insurance because they have young kids and day care costs that could be

higher if one spouse passed away. It's hard for a lot of people to have

saved enough to take care of their family without life insurance if

someone passes away."

"It's

important for people in their 40s to do an insurance-needs analysis,"

Corey says. "Often, people in this age group need a lot of life

insurance because they have young kids and day care costs that could be

higher if one spouse passed away. It's hard for a lot of people to have

saved enough to take care of their family without life insurance if

someone passes away."

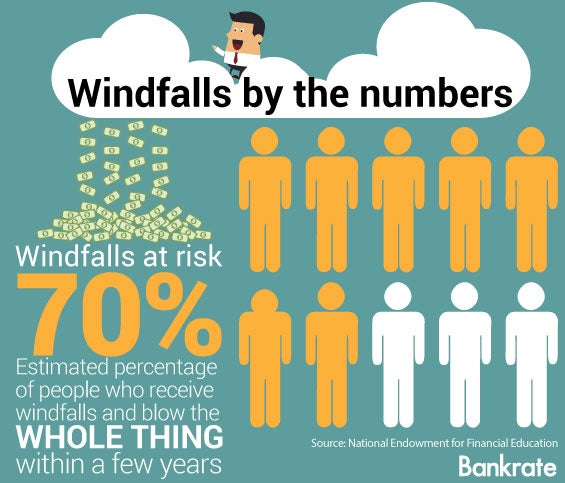

Bradley

says such problems stem from the fact that most people don't understand

the limits of their new wealth, especially if the windfall is

relatively large.

Bradley

says such problems stem from the fact that most people don't understand

the limits of their new wealth, especially if the windfall is

relatively large.